Football, Misdirection and Lying

The Catholic Intellectual Tradition has a long and complicated history in regard to what constitutes lying. Thinkers like Saint Thomas Aquinas and Saint Augustine hold the position that it's never morally justifiable to tell a lie. The speech act is meant to communicate truth. Intentionally communicating things that are ordered towards deception is disordered. Lying, or deceptive communication, is always wrong, then. Just like with any wrongdoing, there are different levels to how grave the wrongdoing is.

There is debate within this tradition as to how much information needs to be given. When someone walks past me in a store and says, “how are you today?,” a long response detailing the state of my gallbladder is probably not in keeping with that conversation. Similarly, jokes are not considered to be lies, even though they involve momentary deception. So, there is an acceptance that different types of conversations warrant different types of responses.

Clearly, we communicate more than just with words. If I stand up and walk briskly at you with an angry expression while rolling up my sleeves, your assumption will probably be that I’m going to confront you.

Thinking about lying through the lens of action leads to some other significant questions. For example, in military battles, there are often attempts at deception. Deception is useful for protecting soldiers through camouflage, aiding in ambush, or in surprising an enemy. False Flag Operations in Naval Battles are a good example. Navy’s used to acquire enemy flags and raise them on their own ships, in an attempt to trick enemies into thinking they are passing a friendly ship. Once the enemy ship gets within range, the ship can attack. All of these can be defended as examples of lying, even though speech isn't involved.

From the traditional perspective it would seem to be immoral to engage in this kind of military deception.

As an assistant football coach, I’ve been thinking about another implication of this discussion. It is common for football teams to utilize misdirection. Oftentimes teams will call plays with the aim of tricking the defense. Football fans will be familiar with things like fake punts, surprise onside kicks, and flea flickers. All of these use pretty drastic means of deceiving opponents about what kind of play is coming.

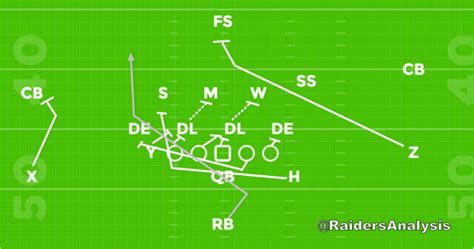

Even beneath these drastic types of plays, there are even more simple plays that seem aimed at deception. Counter plays for example look to show a run in one direction to get defensive players to over pursue in one direction, and then to run the actual play in the opposite direction. Similarly, play action passes are aimed at making defensive players think a run is coming, or at least freezing them to think about it, so that you can create space for receivers to get open for a passing play.

Thinking about these means of misdirection seems to be immoral from a traditional perspective. These plays intentionally deceive defenses into thinking one thing is coming, so that offenses can take advantage of it. Similar to military deception, this seems to involve lying.

However, I stated above that even this traditional perspective on lying holds that particular kinds of discourse allow for more flexibility here. Joking, for example, allows for momentary deception for the goods of laughter and friendship. I also gave the example of simple greetings. When we ask how someone is doing, we are surprised to hear a thoughtful and deep answer to that. We all know someone that overshares things about themselves, that don't seem in keeping with the kind of conversation being had. If this principle holds for speech, it should hold for other kinds of communication too. The example I gave earlier of approaching someone angrily looks different depending on the situation. If you just threw a baseball at the back of their head, that’s a different kind of situation than if you attached him to a long email chain he doesn’t want to be a part of. In the former case, you can expect a confrontation, in the latter case, you might suspect he’s pretending to be angry for a laugh.

So, a principle that seems to be at play here is that we can identify the parameters around different types of communication and respond accordingly. In football, it is clear to everyone involved that it is a game. Two teams are competing to score more points than their opponent. It follows from this that offenses can use misdirection to try to help them move the football. And so, it seems that misdirection is justified, and even enhances the competition. In the same way that jokes and appropriate dialogue enhance relationships, misdirection ups the stakes of football and makes the competition all the better.